Ikebana Schools

Ikebana is a living art with many schools, each with its own philosophy, techniques, and aesthetic focus. Every practitioner can discover a style that speaks to them, while also appreciating the artistry of others.

A Brief Story

Admiration for flowers is universal. In Japan, Shinto revered nature, and Buddhism incorporated flowers as offerings in temples. Over time, these offerings evolved into a sophisticated art form.

In the Heian period (784–1185), flowers were at the heart of playful gathering. Aristocrats enjoyed hana awase (花合わせ), lively contests that compared the beauty of different blossoms. By the Muromachi period, these playful games had grown into grander occasions. Noble families hosted hana gyokai (花御会), flower festivals that combined these games with Buddhist ceremonies like Shisseki Houraku (七夕法楽), and the hana gyokai became a regular festival in the shogun's residence. Early flora arrangements, such as tatehana (立花), took inspiration from Buddhist altar offerings, adorning poetry gatherings where waka (和歌; 'Japanese poem') and renga (連歌, linked poem) were recited.

As centuries passed, Ikebana developed new layers of meaning and style. In the Edo period (1603-1868), tatehanna evolved into the elaborate style rikka (立花) , which adorned samurai residences as ceremonial displays. Yet Ikebana was not reserved for the elite; simpler forms like nageirebana (抛入れ花) and seika (生花) became popular in the more modest machiya townhouses (町家).

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 open Japan to the world and brought Western influences in. This era also gave rise to moribana (盛花), a fresh style that became immensely popular, and Ikebana was incorporated into girls' school curriculums, and soon the art was carried far beyond Japan's shores. Today, Modern Ikebana schools range from traditional to avant-garde styles, and millions of people around the world practise Ikebana as both an art form and a cultural expression.

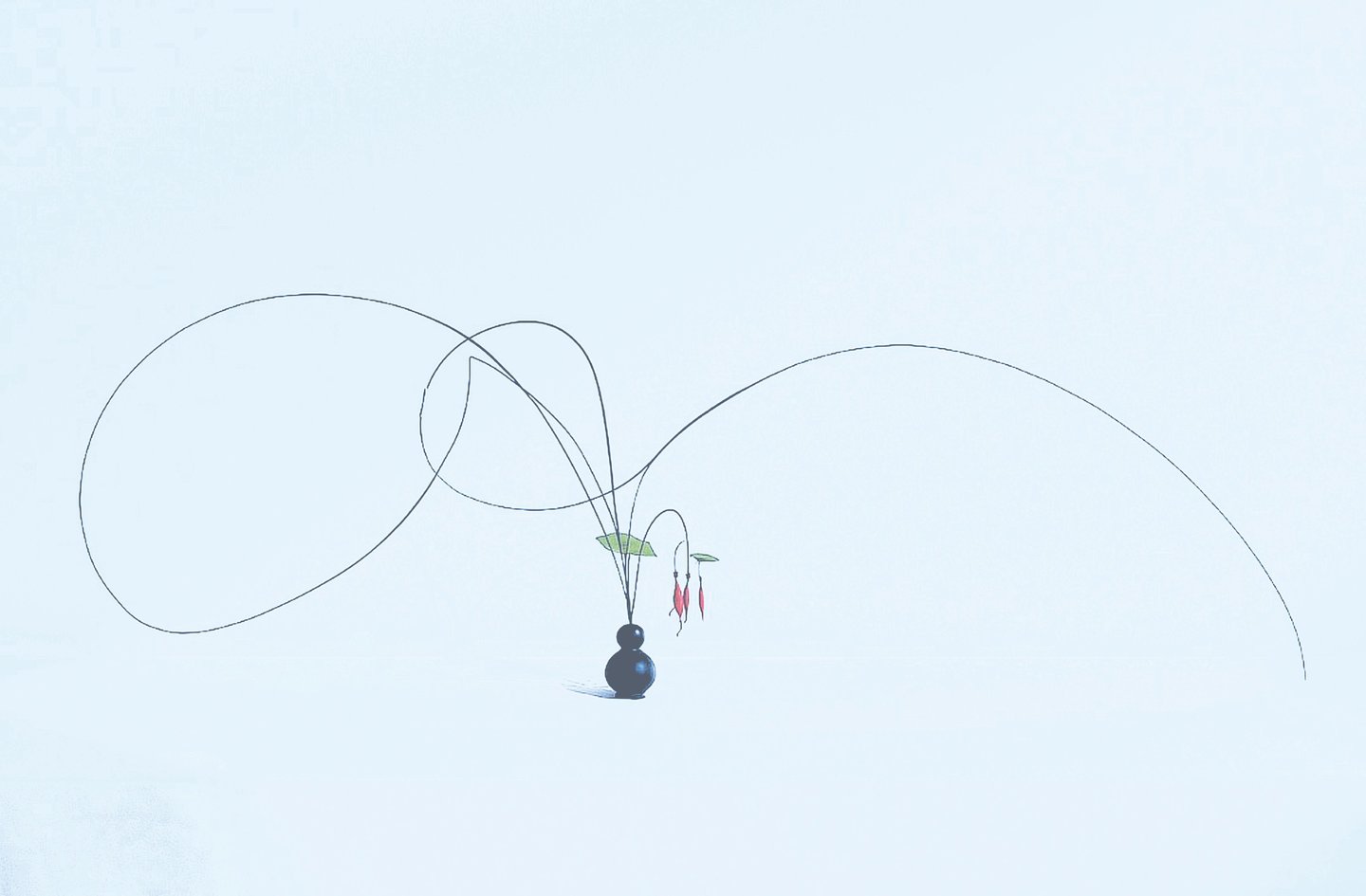

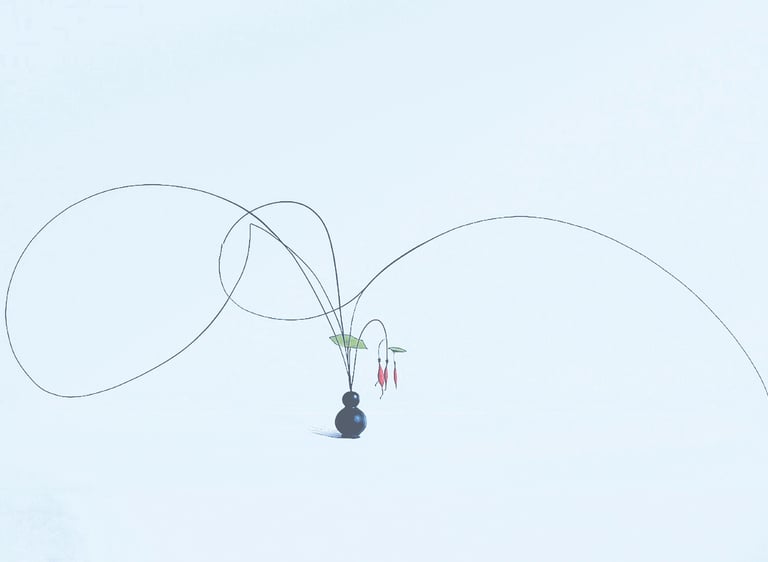

Satsuki, Ikebana awase, 19th Century

Ikebana (生け花) is the Japanese art of flower arranging, literally “living flowers.” More than decoration, ikebana seeks harmony between nature, space, and human sensibility. It emphasises balance, simplicity, and the beauty of impermanence, using seasonal materials such as flowers, branches, and leaves arranged with attentiveness to form and meaningful space. The meditative practice of Ikebana is called Kadō (華道), the “Way of Flowers,” and those who practises it are known as Kadōka (華道家).

An Ikebana arrangement is a living artwork inspired by nature. Harmony is its essence, it brings calm, invites reflection, and celebrates the natural rhythm of life. Ikebana is ever-evolving: modern expressions can be abstract and bold, while traditional styles have captivated viewers for centuries. Though each school has its own style, all share the same core principles of creativity, mindfulness, and a deep connection with nature.

Ikebana across

Cultures

As both cultural heritage and living art, Ikebana creates a dialogue between tradition and contemporary expression.

Evolving Heritage: a heritage practice remains vibrant and innovative across centuries.

Ikebana without Borders: Ikebana encourages collaboration across art forms and cultures, linking Japanese aesthetics with global creativity.

Engage with Ikebana Workshops and demonstrations invite participation, offering mindful encounters with nature and the art of presence.

Global Blossoms: Ikebana continues to foster cultural understanding, embodying “friendship through flowers” across borders.